Mad Max

| Mad Max | |

|---|---|

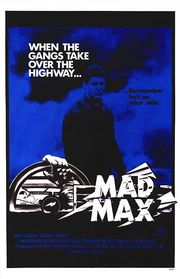

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | George Miller |

| Produced by | Byron Kennedy Bill Miller |

| Written by | George Miller Byron Kennedy James McCausland |

| Starring | Mel Gibson Steve Bisley Joanne Samuel Hugh Keays-Byrne Tim Burns Geoff Parry |

| Music by | Brian May |

| Cinematography | David Eggby |

| Editing by | Cliff Hayes Tony Paterson |

| Studio | Kennedy-Miller Productions |

| Distributed by | Village Roadshow Pictures (Australia) American International Pictures (United States) |

| Release date(s) | 12 April 1979 |

| Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | A$400,000 (est)[1] |

| Gross revenue | $100,000,000 |

| Followed by | Mad Max 2 |

Mad Max is a 1979 Australian dystopian action film directed by George Miller and written by Miller and Byron Kennedy. The film's starring role is played by the then relatively unknown Mel Gibson. Its narrative based around the traditional western genre, Mad Max tells a story of breakdown of society, murder, and vengeance. It became a top-grossing Australian film and has been credited for further opening up the global market to Australian New Wave films. The film was also notable for being the first Australian film to be shot with a widescreen anamorphic lens.

It has had a lasting influence on apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction. The first in the Mad Max franchise, Mad Max spawned sequels Mad Max 2 (known in the United States as The Road Warrior) in 1981 and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome in 1985. The fourth film in the series, tentatively titled Mad Max 4: Fury Road, is in production.

Contents |

Plot

The film opens "A Few Years From Now..." in Australia, in a dystopian future where law and order has begun to break down at the end of the 'Oil Age'. Berserk motorcycle gang member, Crawford "Nightrider" Montizano, has broken police custody and – with a punk woman by his side – is attempting to flee from the Main Force Patrol (MFP), the Federal highway police unit, in a stolen MFP Pursuit Special. Though he manages to elude his initial pursuers, the Nightrider then encounters the MFP's "top pursuit man," leather-clad Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson). Max, the more skilled driver, pursues the Nightrider in a high-speed nerve-racking chase which results in the death of the Nightrider and the woman in a fiery car crash.

Nightrider's Armalite motorcycle gang – led by the barbaric "Toecutter" (Hugh Keays-Byrne) and his lieutenant Bubba Zanetti (Geoff Parry) – is running roughshod over a country town, vandalizing property, stealing fuel and terrorising the local population. Max and his fellow officer Jim 'The' Goose (Steve Bisley) are able to arrest the Toecutter's young protege, Johnny the Boy (Tim Burns), when Johnny lingers at the scene of one of the gang’s crimes, the rape of a young couple. However, when no witnesses show for his trial, the courts declare the case not able be prosecuted and Johnny is released. A shocked Goose attacks Johnny and must be physically restrained; both Goose and Johnny shout threats of revenge at each other. After Bubba drags Johnny away, MFP Captain Fifi Macaffee (Roger Ward) frees his officers to pursue the gangs as they want, "so long as the paperwork's clean."

Shortly thereafter, Johnny sabotages Goose's MFP motorcycle; the motorcycle locks up at high speed the next day, throwing Goose from the bike. Goose is unharmed, though his bike is badly damaged; he borrows a ute to haul his bike back to civilization. However, Johnny and the Toecutter's gang are waiting further up the highway in ambush. Johnny throws a brake drum at Goose's windshield, causing him to run off the road; then – upon the Toecutter's insistence, and perhaps as a gang initiation – Johnny is instructed to throw a match at Goose's ute, which is leaking petrol from its ruptured fuel line. Johnny refuses, and the Toecutter starts to abuse him; in the ensuing argument, the lit match is thrown and lands in the wreckage of the ute, which erupts in flames.

The Goose is mortally wounded, and after seeing his charred body in the hospital's burn ward, Max becomes angry and disillusioned with the police force. Worried of what may happen if he stays in the job, and fearing he may become as savage and brutal as the gang members, Max announces to Fifi that he is resigning from the MFP with no intention of returning. Fifi convinces him to take a holiday first before making his final decision about leaving.

While on holiday at the coast, Max's wife, Jessie (Joanne Samuel), and their son run into Toecutter's gang, who attempt to molest her. She flees, but the gang later manages to track them to the remote farm near the beach where she and Max are staying. While attempting to escape, Jessie and her son are run down and over by the gang; their crushed bodies are left in the middle of the road. Max arrives too late to intervene.

Filled with obsessive rage, Max dons his police leathers and takes a supercharged black Pursuit Special to pursue the gang. After torturing a mechanic for information on the gang, Max methodically hunts down and kills the gang members: several gang members are forced off a bridge at high speed; Max shoots and kills Bubba at point blank range with his shotgun; the Toecutter is forced into the path of a speeding semi-trailer truck and crushed. In the road battles, Max has his arm crushed when it is run over by Bubba Zanetti's motorbike, and receives a gunshot wound to his knee, which he braces with a makeshift splint. Becoming even more relentless and ruthless, he searches for the final members of the gang. When Max finds Johnny taking the boots off a dead driver at the scene of a crash, he handcuffs Johnny's ankle to the wrecked vehicle and sets a crude time-delay fuse. Throwing Johnny a hacksaw, Max leaves him the choice of sawing through either the hi-tensile steel of the handcuffs (which will take ten minutes) or his ankle (which will take five minutes). As Max drives away, the vehicle explodes; an emotionless Max drives on further into the Outback without turning back.

Conception and production

George Miller was a medical doctor in Victoria, Australia, working in a hospital emergency room, where he saw many injuries and deaths of the types depicted in the film. While in residency at a Melbourne hospital, he met amateur filmmaker Byron Kennedy at a summer film school in 1971. The duo produced a short film, Violence in the Cinema, Part 1, which was screened at a number of film festivals and won several awards. Eight years later, the duo created Mad Max, with the assistance of first time screenwriter James McCausland (who appears in the film as the bearded man in an apron in front of the diner). Some have speculated that Miller's medical background is reflected in the name of his chief character Max Rockatansky, perhaps a reference to Baron Carl von Rokitansky, who developed the most common procedure used to remove the organs at autopsy[2]

Miller believed that audiences would find his violent story to be more believable if set in a bleak, dystopic future. The film was shot over a period of twelve weeks in Australia, between December 1978 and February 1979, in and around Melbourne. Many of the car-chase scenes for the original Mad Max were filmed near the town of Lara, just north of Geelong. The movie was shot with a widescreen anamorphic lens, the first Australian film to use one.

| “ | George and I wrote the [Mad Max] script based on the thesis that people would do almost anything to keep vehicles moving and the assumption that nations would not consider the huge costs of providing infrastructure for alternative energy until it was too late. | ” |

|

—James McCausland, writing on peak oil in The Courier-Mail, 2006[3] |

||

Mel Gibson, a complete unknown at this point, went to auditions with his friend and classmate, Steve Bisley (who would later land the part of Jim Goose). Gibson went to auditions in poor shape, as the night before he had got into a drunken brawl with three men at a party, resulting in a swollen nose, a broken jawline, and various other bruises. Gibson showed up at the audition the next day looking like a "black and blue pumpkin" (his own words). He did not expect to get the role and only went to accompany his friend. However, the casting agent liked the look and told Gibson to come back in two weeks, telling him "we need freaks." When Gibson returned, he was not recognised because his wounds had healed almost completely; he received the part anyway.[4]

Due to the film's low budget (A$400,000), only Gibson was given a jacket and pants made from real leather. All the other actors playing police officers wore vinyl outfits. The police cars were repeatedly repainted to give the illusion that more cars were used; often they were driven with the paint still wet.

The film's post-production was done at Kennedy's house, with Wilson and Kennedy editing the film in Kennedy's bedroom on a home-built editing machine that Kennedy's father, an engineer, had designed for them. Wilson and Kennedy also edited the sound there.

Vehicles

Max's yellow Interceptor was a 1974 Ford Falcon XB sedan (previously, a Melbourne police car) with a 351ci Cleveland V8 engine and many other modifications.[5]

The Big Bopper, driven by Roop and Charlie, was also a 1974 Ford Falcon XB sedan and former Victorian Police car, but was powered by a 302cid V8.[6] The March Hare, driven by Sarse and Scuttle, was an in-line-six-powered 1972 Ford Falcon XA sedan (this car was formerly a Melbourne taxi cab).[7]

The most memorable car, Max's black Pursuit Special was a limited GT351 version of a 1973 Ford XB Falcon Hardtop (sold in Australia from December 1973 to August 1976) which was primarily modified by Murray Smith, Peter Arcadipane and Ray Beckerley.[8] After filming of the first movie was completed, the car was handed over to Murray Smith. When production of Mad Max 2 (The Road Warrior) began the car was again purchased back by George Miller for use in the sequel. Once filming was over the car was left at a wrecking yard and was bought and restored by Bob Forsenko, and is currently on display in the Cars of the Stars Motor Museum in Cumbria, England.[9]

The Nightrider's vehicle, another Pursuit Special, was a 1972 Holden HQ LS Monaro coupe.[10]

The car driven by the young couple that is destroyed by the bikers is a 1959 Chevrolet Impala sedan.[11]

Of the motorcycles that appear in the film, 14 were KZ1000s donated by Kawasaki. All were modified in appearance by Melbourne business La Parisienne - one as the MFP bike ridden by 'The Goose' and the balance for members of the Toecutter's gang, played in the film by members of a local Victorian motorcycle club, the Vigilantes.[12]

By the end of filming, fourteen vehicles had been destroyed in the chase and crash scenes, including the director's personal Mazda Bongo (the small, blue van that spins uncontrollably after being struck by the Big Bopper in the film's opening chase).

Reception

The film initially received mostly positive reviews from critics. Tom Buckley of The New York Times called it "ugly and incoherent",[13] though Variety magazine praised the directorial debut by Miller.[14] As of April 2010, the film had a 95% "Fresh" rating on the Rotten Tomatoes,[15] and is considered by many as one of the best films of 1979.[16][17][18] In 2004, The New York Times placed the film on its Best 1000 Movies Ever list.[19]

Though the film had a limited run in the United States and earned only $8 million there, it did very well elsewhere around the world and went on to earn $100 million worldwide.[20] Since it was independently financed with a reported budget of just A$400,000, it was a major financial success. For twenty years, the movie held a record in Guinness Book of Records as the highest profit-to-cost ratio of a motion picture, conceding the record only in 1999 to The Blair Witch Project.[21] The film was awarded three Australian Film Institute Awards in 1979 (for editing, sound, and musical score). It was also nominated for Best Film, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor (Hugh Keays-Byrne) by the AFI. The film also won the Special Jury Award at the Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival.[22]

Release

When the film was first released in the United States, all the voices, including that of Mel Gibson's character, were dubbed by American performers at the behest of the distributor, American International Pictures, for fear that audiences would not take warmly to actors speaking entirely with Australian accents. Much of the Australian slang and terminology was also replaced with American usages (examples: "See looks!" became "See what I see?", "windscreen" became "windshield", "very toey" became "super hot", and "proby" -probationary officer- became "rookie"). AIP also altered the operator's duty call on Jim Goose's bike in the beginning of the movie (it ended with "Come on, Goose, where are you?"). The only dubbing exceptions were the voice of the singer in the Sugartown Cabaret (played by Robina Chaffey), the voice of Charlie (played by John Ley) through the mechanical voice box, and Officer Jim Goose (Steve Bisley), singing as he drives a truck before being ambushed.

The original Australian dialogue track was finally released in North America in 2000 in a limited theatrical reissue by MGM, the film's current rights holders (it has since been released in the U.S. on DVD with both the US and Australian soundtracks on separate tracks).

Since Mel Gibson was not well known to American audiences at the time, trailers and TV spots in the USA emphasized the film's action content.

Both New Zealand and Sweden initially banned the film.[23]

Legacy

James Wan and Leigh Whannell credit the film's final scene, in which Johnny is given the option of cutting off his own foot to escape, for inspiring the entire Saw series.[24]

See also

- 1979 in film

- Cinema of Australia

- Australian films of 1979

References

- ↑ "Mad Max : SE". DVD Times. 2002-01-19. http://www.dvdtimes.co.uk/content.php?contentid=4134. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ Biber, Katherine (2001). "The Threshold Moment: Masculinity at Home and on the Road in Australian Cinema" (PDF). Limina. University of Western Australia. http://www.limina.arts.uwa.edu.au/__data/page/61289/biber_new.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ James McCausland (4 December 2006). "Scientists' warnings unheeded". The Courier-Mail (News.com.au). http://www.news.com.au/couriermail/story/0,23739,20870561-3122,00.html. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ Mary Packard and the editors of Ripley Entertainment, ed (2001). Ripley's Believe It or Not! Special Edition. Leanne Franson (illustrations) (1st ed. ed.). Scholastic Inc.. ISBN 0-439-26040-X.

- ↑ "Mad Max Cars—Max's Yellow Interceptor (4 Door XB Sedan)". Madmaxmovies.com. http://www.madmaxmovies.com/cars/madmax/YellowInterceptor/index.html. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Cars—Big Boppa/Big Bopper". Madmaxmovies.com. http://www.madmaxmovies.com/cars/madmax/BigBopper/index.html. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Cars—March Hare". Madmaxmovies.com. http://www.madmaxmovies.com/cars/madmax/MarchHare/index.html. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Movies—The History of the ''Interceptor'', Part 1". Madmaxmovies.com. http://www.madmaxmovies.com/cars/interceptor/history1.html. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "Cars of the Stars Motor Museum". Carsofthestars.com. http://www.carsofthestars.com/. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Cars—The Nightrider's Monaro". Madmaxmovies.com. http://www.madmaxmovies.com/cars/madmax/Nightrider/index.html. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Cars—Chevy Impala". Madmaxmovies.com. http://www.madmaxmovies.com/cars/madmax/ChevyImpala/index.html. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ "''Mad Max'' Cars—Toecutter's Gang (Bikers)". Madmaxmovies.com. http://www.madmaxmovies.com/cast/MadMax/Bikers/index.html. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ Buckley, Tom (14 June 1980). "Mad Max". The New York Times. http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=EE05E7DF173BBB2CA7494CC6B6799C836896. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ By (1979-01-01). "Mad Max Review - Read Variety's Analysis Of The Movie Mad Max". Variety.com. http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117792854.html?categoryid=31&cs=1&p=0. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Mad Max". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/mad_max/. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ "The Best Movies of 1979 by Rank". Films101.com. http://www.films101.com/y1979r.htm. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Best Films of 1979". Listal.com. http://www.listal.com/list/best-films-of-1979. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Most Popular Feature Films Released in 1979". IMDb.com. http://www.imdb.com/year/1979/. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. April 29, 2003. http://www.nytimes.com/ref/movies/1000best.html. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Mad Max". The Numbers. http://www.the-numbers.com/movies/1980/0MMX1.php. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑

- ↑ Mad Max (1979)—Awards

- ↑ Carroll, Larry (2009-02-03). "Greatest Movie Badasses Of All Time: Mad Max - Movie News Story | MTV Movie News". Mtv.com. http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1604110/20090202/story.jhtml. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ↑ McDonough, Maitland. "Not Quite Hollywood: the Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation!". Film Journal International. Vol. 112, no. 8., Aug. 2009. p.73

External links

- Official website – Home to the original Mad Max movie, maintained by members of the cast and crew.

- Mad Max at the Internet Movie Database

- Mad Max at the TCM Movie Database

- Mad Max at Allmovie

- Mad Max at Rotten Tomatoes

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||